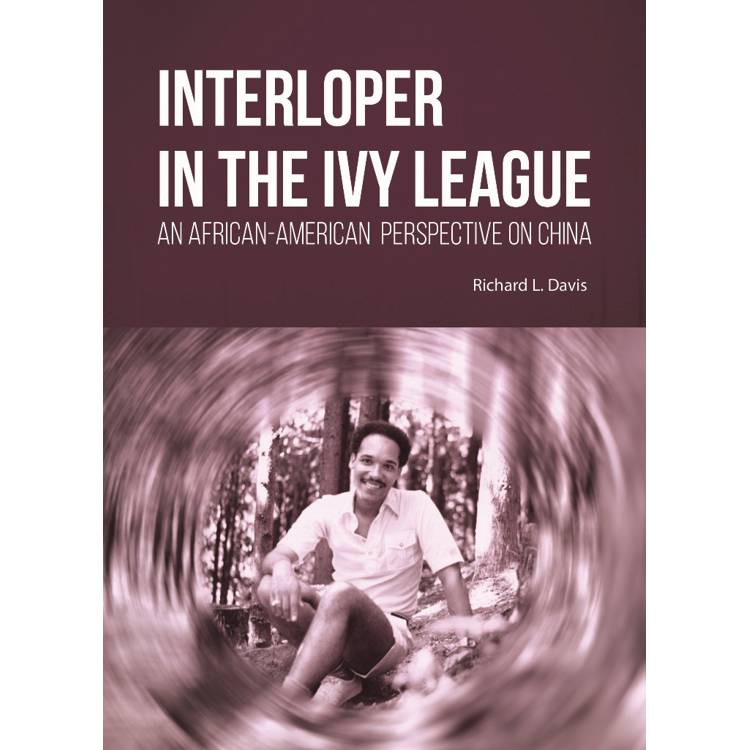

Interloper in the Ivy League: An African-American Perspective on China

非裔美國人眼中的中國

活動訊息

內容簡介

As an historian and interloper in the Ivy League, I see the world through the lens of my unique identity, where the flow of history and personal struggles intertwine.

Growing up in a poor foster family, Richard L. Davis carved an extraordinary path through academia to become a distinguished historian of ancient China. Despite facing significant challenges and exclusion, he secured advanced degrees and taught at some of the top universities—an achievement nearly impossible in his generation.

Within predominantly white academic institutions, he—the interloper in the Ivy League—offers a fair yet compassionate judgment of elite universities undermined by systemic and structural flaws. He reveals how these remarkably homogenous institutions are biased power structures based on pedigree, race, and personal connections, which restrict opportunities for individuals from diverse backgrounds.

More than a record of his academic path, the memoir acknowledges the deep impact of those who greatly supported him. His identity as a gay Black with a public school background often led to questions being raised about his qualifications and abilities, with missed opportunities as a result. His mentors, friends and lovers became sources of special strength at those times, helping him to overcome challenges and break through the boundaries. In addition, through the lens of a historian, he reflects on the evolving landscapes these past several decades of Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China, places where he has lived and witnessed firsthand.

Growing up in a poor foster family, Richard L. Davis carved an extraordinary path through academia to become a distinguished historian of ancient China. Despite facing significant challenges and exclusion, he secured advanced degrees and taught at some of the top universities—an achievement nearly impossible in his generation.

Within predominantly white academic institutions, he—the interloper in the Ivy League—offers a fair yet compassionate judgment of elite universities undermined by systemic and structural flaws. He reveals how these remarkably homogenous institutions are biased power structures based on pedigree, race, and personal connections, which restrict opportunities for individuals from diverse backgrounds.

More than a record of his academic path, the memoir acknowledges the deep impact of those who greatly supported him. His identity as a gay Black with a public school background often led to questions being raised about his qualifications and abilities, with missed opportunities as a result. His mentors, friends and lovers became sources of special strength at those times, helping him to overcome challenges and break through the boundaries. In addition, through the lens of a historian, he reflects on the evolving landscapes these past several decades of Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China, places where he has lived and witnessed firsthand.

目錄

Preface

Chapter 1 The Other New York

Childhood, School Years, Undergraduate Years, First Stay in Taiwan, “Roots” in Miniature, A Memorable Jewish Mentor, A Slice of Heaven – Princeton, Graduate School Mentors, Cracks in Heaven, Back to Taipei, The Last Stretch, Loveless, The Southern Ivy

Chapter 2 From Vermont to the Carolinas

Freshman Teacher at Middlebury, The Duke Years, Crème of the African American Crop, Academic Routine at Duke, President Sanford, Program Building, The Trials of Publishing, The Other China, Africans in China, Gay Life in China, America Again, The Other Cambridge, Milking the Poor, Cutting Loose

Chapter 3 Early Years at Brown University

The Poorest Ivy, The Longest June, Brown Women, Academic Environment, Making a Difference, Wealth and Beauty, Wind Against the Mountain, Taiwan Again, Surviving the Plague

Chapter 4 Late Career at Brown University

Tumult in the President’s Office, Spousal Hires, Herding Cats, Social Life, Historical Records Project, The Simmons’ Administration, Chairing East Asian Studies, Tenure Controversies, Imperial Biography, Leaving America

Chapter 5 Hong Kong Decade

A Willful Bondage, University Leaders, Breaking into the Chinese Market, Remembering Zhang Qifan, A New Biography, Legacy in the Classroom, Provincialism of Faculty, The Reluctant Head, Role Model, As Embattled Dean, Personal Life

Chapter 1 The Other New York

Childhood, School Years, Undergraduate Years, First Stay in Taiwan, “Roots” in Miniature, A Memorable Jewish Mentor, A Slice of Heaven – Princeton, Graduate School Mentors, Cracks in Heaven, Back to Taipei, The Last Stretch, Loveless, The Southern Ivy

Chapter 2 From Vermont to the Carolinas

Freshman Teacher at Middlebury, The Duke Years, Crème of the African American Crop, Academic Routine at Duke, President Sanford, Program Building, The Trials of Publishing, The Other China, Africans in China, Gay Life in China, America Again, The Other Cambridge, Milking the Poor, Cutting Loose

Chapter 3 Early Years at Brown University

The Poorest Ivy, The Longest June, Brown Women, Academic Environment, Making a Difference, Wealth and Beauty, Wind Against the Mountain, Taiwan Again, Surviving the Plague

Chapter 4 Late Career at Brown University

Tumult in the President’s Office, Spousal Hires, Herding Cats, Social Life, Historical Records Project, The Simmons’ Administration, Chairing East Asian Studies, Tenure Controversies, Imperial Biography, Leaving America

Chapter 5 Hong Kong Decade

A Willful Bondage, University Leaders, Breaking into the Chinese Market, Remembering Zhang Qifan, A New Biography, Legacy in the Classroom, Provincialism of Faculty, The Reluctant Head, Role Model, As Embattled Dean, Personal Life

序/導讀

Preface

My journey from the South Side of Buffalo, New York, to the academy’s highest rungs as a China historian of African American descent is the focus of this book, a journey marked by a record of scholarship with few rivals in the Western world, but also frustrations with the ways of the academy. It would have been impossible a generation ago for the product of lesser-known public schools to secure advanced degrees from Princeton and teach at some of the country’s leading institutions of higher education – Middlebury, Duke, and Brown – before capping my career with a well-deserved Chair Professorship in Hong Kong.

I have worked with every sort of university administrator, from the charismatic and visionary to the occasional mediocrity with little in the way of substance. I was also privileged to claim some of the most iconic historians of our time as colleagues and friends. When I received the PhD in 1980, African Americans employed by Ivy League institutions like Princeton represented roughly one percent of the faculty, virtually all teaching some aspect of the African American experience. When I arrived at Brown nine years later, only one or two individuals studied other cultures. The African American faculty today has grown in numbers, but the vast majority of humanists still teach subjects related to their own life experiences, which is a disservice to students of all backgrounds.

Yet the higher I rose in America’s academy, I grew appalled by the self-interestedness of academics: the grip of a handful of individuals over the industry’s leading institutions, poor judgment in hiring and promoting faculty, and even poorer judgment in dealing with the consequences of bad decisions over the years. The lack of professionalism that leads to personalizing every decision is a threat to the well-being of any university, and the Ivy League elite should abide by the best practices in the industry, not the worst.

East Asian Studies at Princeton was once a place of rare opportunity for an aspiring academic like me, due to a cluster of senior faculty at the peak of their creative energies who doubled as resources in the profession. But I also witnessed the unraveling of the very same program through indefensible decisions on staffing, as a consequence of a leadership vacuum within and the failure of successive administrations to intervene. I am critical of Princeton because I genuinely care. My concern extends to the State University of New York, where a well-intended governor nearly doomed a promising state system by setting unreasonable ceilings on tuition, which ultimately undercut the academic standing of its flagship institution and caused the hemorrhaging of faculty with options. The issue of higher education costs emerged in America’s 2016 election debates and the calls for tuition-free state universities proved similarly misguided. Quality education is never cheap and educators, not politicians, should lead any attempt at reform. Otherwise, publicly funded universities will always play second fiddle to the private.

The tenure system presents another source of frustration. Colleges and universities need to reassess a system that offers lifetime contracts after six short years of employment, too soon to make informed decisions about future promises. Even the best universities get it wrong most of the time! My experience at private institutions in America and public universities abroad has shown that tenure does little to protect academic freedom, its original purpose, but merely protects the weakest members of our fraternity, while creating a subculture given to rewarding every sort of eccentricity. Meanwhile, the existence of the tenure allows universities to dole out lower salaries for all but a handful of stars. In Hong Kong, academic salaries were historically tied to the civil service, as in the UK, allowing the salary scales for university professors to parallel senior civil servants. Needless to say, compensation for Chair Professors is even more competitive, which is why the city is able to attract some of the industry’s top talent. In this way, faculty members have no need to expend enormous energy attracting outside offers to earn the salaries they deserve.

As someone who earned his Chair Professorship through years of sweat, I am appalled by the decline in standards for admission to those once illustrious ranks, due to the proliferation of endowed chairs, especially at the leading Ivy League institutions, where the position has lost all distinction, after successive administrations organized capital campaigns around faculty enhancement and now have chairs for which they must lower standards to fill. The net result is a decline in the national ratings for many of those institutions. Too much funding for chairs is restricted to a specific area of interest within a given discipline, even though disciplines are constantly changing and Departments need the flexibility to move resources to reflect those changes or they run the risk of losing their best faculty to rival institutions, as occurred in my case at Brown.

Apart from placing the academy under a critical eye, I aspire in the following pages to acknowledge that the bulk of my achievements in the profession, and the many small pleasures I have known in my private life, can never be separated from who I am as a gay man. Life has challenged me to navigate a multitude of headwinds as a poor man in a profession that values pedigree and a subculture that requires resources beyond the means of most academics. My partners in life have been sources of special strength in the face of these challenges. I have discussed those persons and experiences in my private life that bear some relevance to the larger story. Every companion has been a different kind of resource precisely because they were as different from me as from one another. I also proudly acknowledge the outreach of a long line of gay students over the years and shared their anxieties, teaching me much about myself in the process.

A third lens through which I view the world is as an African American, for whom prejudice of any sort is unacceptable and the range of my professional experience has provided a special window on race in the academy. For a quarter-century, I worked at institutions with fairly liberal faculties, yet they somehow still managed to recruit colleagues much like themselves in terms of race and class, usually without conscious effort. Affirmative Action has helped to insulate me from the worst in bias against people like me, but the power structure remains remarkably homogenous. The latest target of bias in America is the expat from mainland China, the prejudice that appeared in academic circles even before infiltrating the wider society. Hong Kong proved even more hostile to the Chinese expat, I could only conclude, as my tenure as Chair

Professor came to a close, albeit for different reasons.

Historians take pride in their ability to elevate the human spirit through biography, the oldest genre in our profession, where we breathe life into the dead through a few well-chosen words. We are nonetheless far better at scrutinizing the lives of others than reflecting back on our own, a highly subjective space for someone with aspirations of objectivity. My motivation emanates less from the urge for self-aggrandizement and more from the need to celebrate the teachers I most revere, the institutions I most respect, and the friends I most cherish – without whom my time on this earth would have mattered little.

Some months ago, a woman working in the University of Buffalo library during my student days, Audrey Morris, died at ninety-five in a Florida retirement home. Her belongings included a big box of letters and cards received from me over the years. “She lived vicariously by your adventures,” her son Allen said, before thanking me for the friendship. The letter served as a reminder of my earliest fans back in Buffalo, who gave me the confidence to thrive in this highly competitive profession, along with the courage to stand for principle.

Richard L. Davis

Taipei, January 2018

My journey from the South Side of Buffalo, New York, to the academy’s highest rungs as a China historian of African American descent is the focus of this book, a journey marked by a record of scholarship with few rivals in the Western world, but also frustrations with the ways of the academy. It would have been impossible a generation ago for the product of lesser-known public schools to secure advanced degrees from Princeton and teach at some of the country’s leading institutions of higher education – Middlebury, Duke, and Brown – before capping my career with a well-deserved Chair Professorship in Hong Kong.

I have worked with every sort of university administrator, from the charismatic and visionary to the occasional mediocrity with little in the way of substance. I was also privileged to claim some of the most iconic historians of our time as colleagues and friends. When I received the PhD in 1980, African Americans employed by Ivy League institutions like Princeton represented roughly one percent of the faculty, virtually all teaching some aspect of the African American experience. When I arrived at Brown nine years later, only one or two individuals studied other cultures. The African American faculty today has grown in numbers, but the vast majority of humanists still teach subjects related to their own life experiences, which is a disservice to students of all backgrounds.

Yet the higher I rose in America’s academy, I grew appalled by the self-interestedness of academics: the grip of a handful of individuals over the industry’s leading institutions, poor judgment in hiring and promoting faculty, and even poorer judgment in dealing with the consequences of bad decisions over the years. The lack of professionalism that leads to personalizing every decision is a threat to the well-being of any university, and the Ivy League elite should abide by the best practices in the industry, not the worst.

East Asian Studies at Princeton was once a place of rare opportunity for an aspiring academic like me, due to a cluster of senior faculty at the peak of their creative energies who doubled as resources in the profession. But I also witnessed the unraveling of the very same program through indefensible decisions on staffing, as a consequence of a leadership vacuum within and the failure of successive administrations to intervene. I am critical of Princeton because I genuinely care. My concern extends to the State University of New York, where a well-intended governor nearly doomed a promising state system by setting unreasonable ceilings on tuition, which ultimately undercut the academic standing of its flagship institution and caused the hemorrhaging of faculty with options. The issue of higher education costs emerged in America’s 2016 election debates and the calls for tuition-free state universities proved similarly misguided. Quality education is never cheap and educators, not politicians, should lead any attempt at reform. Otherwise, publicly funded universities will always play second fiddle to the private.

The tenure system presents another source of frustration. Colleges and universities need to reassess a system that offers lifetime contracts after six short years of employment, too soon to make informed decisions about future promises. Even the best universities get it wrong most of the time! My experience at private institutions in America and public universities abroad has shown that tenure does little to protect academic freedom, its original purpose, but merely protects the weakest members of our fraternity, while creating a subculture given to rewarding every sort of eccentricity. Meanwhile, the existence of the tenure allows universities to dole out lower salaries for all but a handful of stars. In Hong Kong, academic salaries were historically tied to the civil service, as in the UK, allowing the salary scales for university professors to parallel senior civil servants. Needless to say, compensation for Chair Professors is even more competitive, which is why the city is able to attract some of the industry’s top talent. In this way, faculty members have no need to expend enormous energy attracting outside offers to earn the salaries they deserve.

As someone who earned his Chair Professorship through years of sweat, I am appalled by the decline in standards for admission to those once illustrious ranks, due to the proliferation of endowed chairs, especially at the leading Ivy League institutions, where the position has lost all distinction, after successive administrations organized capital campaigns around faculty enhancement and now have chairs for which they must lower standards to fill. The net result is a decline in the national ratings for many of those institutions. Too much funding for chairs is restricted to a specific area of interest within a given discipline, even though disciplines are constantly changing and Departments need the flexibility to move resources to reflect those changes or they run the risk of losing their best faculty to rival institutions, as occurred in my case at Brown.

Apart from placing the academy under a critical eye, I aspire in the following pages to acknowledge that the bulk of my achievements in the profession, and the many small pleasures I have known in my private life, can never be separated from who I am as a gay man. Life has challenged me to navigate a multitude of headwinds as a poor man in a profession that values pedigree and a subculture that requires resources beyond the means of most academics. My partners in life have been sources of special strength in the face of these challenges. I have discussed those persons and experiences in my private life that bear some relevance to the larger story. Every companion has been a different kind of resource precisely because they were as different from me as from one another. I also proudly acknowledge the outreach of a long line of gay students over the years and shared their anxieties, teaching me much about myself in the process.

A third lens through which I view the world is as an African American, for whom prejudice of any sort is unacceptable and the range of my professional experience has provided a special window on race in the academy. For a quarter-century, I worked at institutions with fairly liberal faculties, yet they somehow still managed to recruit colleagues much like themselves in terms of race and class, usually without conscious effort. Affirmative Action has helped to insulate me from the worst in bias against people like me, but the power structure remains remarkably homogenous. The latest target of bias in America is the expat from mainland China, the prejudice that appeared in academic circles even before infiltrating the wider society. Hong Kong proved even more hostile to the Chinese expat, I could only conclude, as my tenure as Chair

Professor came to a close, albeit for different reasons.

Historians take pride in their ability to elevate the human spirit through biography, the oldest genre in our profession, where we breathe life into the dead through a few well-chosen words. We are nonetheless far better at scrutinizing the lives of others than reflecting back on our own, a highly subjective space for someone with aspirations of objectivity. My motivation emanates less from the urge for self-aggrandizement and more from the need to celebrate the teachers I most revere, the institutions I most respect, and the friends I most cherish – without whom my time on this earth would have mattered little.

Some months ago, a woman working in the University of Buffalo library during my student days, Audrey Morris, died at ninety-five in a Florida retirement home. Her belongings included a big box of letters and cards received from me over the years. “She lived vicariously by your adventures,” her son Allen said, before thanking me for the friendship. The letter served as a reminder of my earliest fans back in Buffalo, who gave me the confidence to thrive in this highly competitive profession, along with the courage to stand for principle.

Richard L. Davis

Taipei, January 2018

配送方式

-

台灣

- 國內宅配:本島、離島

-

到店取貨:

不限金額免運費

-

海外

- 國際快遞:全球

-

港澳店取:

訂購/退換貨須知

加入金石堂 LINE 官方帳號『完成綁定』,隨時掌握出貨動態:

商品運送說明:

- 本公司所提供的產品配送區域範圍目前僅限台灣本島。注意!收件地址請勿為郵政信箱。

- 商品將由廠商透過貨運或是郵局寄送。消費者訂購之商品若無法送達,經電話或 E-mail無法聯繫逾三天者,本公司將取消該筆訂單,並且全額退款。

- 當廠商出貨後,您會收到E-mail出貨通知,您也可透過【訂單查詢】確認出貨情況。

- 產品顏色可能會因網頁呈現與拍攝關係產生色差,圖片僅供參考,商品依實際供貨樣式為準。

- 如果是大型商品(如:傢俱、床墊、家電、運動器材等)及需安裝商品,請依商品頁面說明為主。訂單完成收款確認後,出貨廠商將會和您聯繫確認相關配送等細節。

- 偏遠地區、樓層費及其它加價費用,皆由廠商於約定配送時一併告知,廠商將保留出貨與否的權利。

提醒您!!

金石堂及銀行均不會請您操作ATM! 如接獲電話要求您前往ATM提款機,請不要聽從指示,以免受騙上當!

退換貨須知:

**提醒您,鑑賞期不等於試用期,退回商品須為全新狀態**

-

依據「消費者保護法」第19條及行政院消費者保護處公告之「通訊交易解除權合理例外情事適用準則」,以下商品購買後,除商品本身有瑕疵外,將不提供7天的猶豫期:

- 易於腐敗、保存期限較短或解約時即將逾期。(如:生鮮食品)

- 依消費者要求所為之客製化給付。(客製化商品)

- 報紙、期刊或雜誌。(含MOOK、外文雜誌)

- 經消費者拆封之影音商品或電腦軟體。

- 非以有形媒介提供之數位內容或一經提供即為完成之線上服務,經消費者事先同意始提供。(如:電子書、電子雜誌、下載版軟體、虛擬商品…等)

- 已拆封之個人衛生用品。(如:內衣褲、刮鬍刀、除毛刀…等)

- 若非上列種類商品,均享有到貨7天的猶豫期(含例假日)。

- 辦理退換貨時,商品(組合商品恕無法接受單獨退貨)必須是您收到商品時的原始狀態(包含商品本體、配件、贈品、保證書、所有附隨資料文件及原廠內外包裝…等),請勿直接使用原廠包裝寄送,或於原廠包裝上黏貼紙張或書寫文字。

- 退回商品若無法回復原狀,將請您負擔回復原狀所需費用,嚴重時將影響您的退貨權益。

商品評價