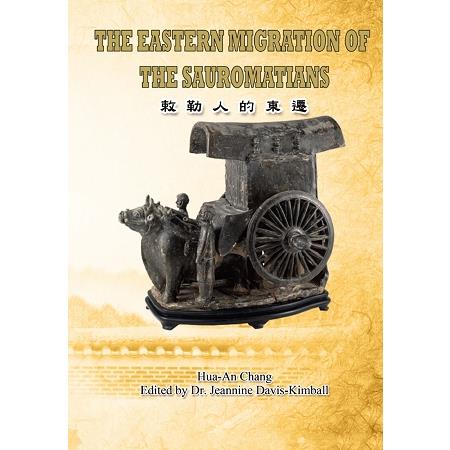

敕勒人的東遷(國際英文版)

The Eastern Migration of Sauromatians

活動訊息

內容簡介

From the time of the "Chaos of the Eight Princes" (291 IV. Modern Western Literatures) in the Western Jin Dynasty, China suffered from civil strife and foreign aggression. After nearly three hundred years the people lived in extreme poverty until Emperor Wen of the Sui Dynasty unified China in 589 CE. The continual strife had created a melting pot and laid the foundation for the subsequent Sui and Tang Dynasties.

Among the many ranks of barbarians that migrated into China, one nomadic tribe - the Sau-ro - has been ignored by classical historians. The correct pronunciation of "敕勒" is "Sau-ro," which is a shortened form of the translated word Sauromatae. Sauromatae is the name of their western homeland, probably modern-day Ukraine. During the mid-4th century, the Sau-ro nomads fled because of a great famine that had overtaken their homeland. They nomadized this great distance to Siberia and Mongolia searching for water and fodder for their flocks. Over time their migration continued, this time toward the south in quest of a more hospitable climate. As to be expected, local nomads with superior mobility and combat effectiveness attacked them along the way. The Sau-ro thus suffered defeat in 399 CE and again in 429 CE. Following these vanquishments the Northern Wei took approximately half-a-million Sau-ros, who had settled in central Mongolia and Trans-Baikal, prisoner. They were then again re-settled on the steppes of Inner Mongolia.

Around 430 CE, approximately another half-a-million Sau-ro, who had now occupid southern and western Siberia, were placed into servitude by the Rou-ran. In 487 CE, the Sau-ro migrated to northern Xinjiang where they established an empire that the Chinese designated Ko-ch. Bad luck was again to strike the Ko-ch people of the Sau-ro Empire for in 551 CE the Tu-jue ambushed and conquered them in Xinjiang Province. The Sau-ro Empire was now decimated. In 630 CE the remaining Ko-ch were re-settled in the Ordos. This filled a void as the Tang Dynasty had annihilated the former inhabitants, the Eastern Tu-jue. Because of heavy taxation and hard labor, the Ko-ch rebelled twice, once in 721 CE and again in 722 CE. Following the suppression of the 722 CE insurrections, the remaining slightly more than 50,000 Sau-ros were then re-settled as farmers in southern Henan Province.

Previously, in 429 CE many Sau-ro had been relocated to the "Six Garrisons" in Inner Mongolia. By 525 CE bureaucratic corruptions had become so oppressive that riots broke out and many Sau-ro were included among the rioters. Because of their loyalty, bravery, wild disposition, and skilled martial arts, a number of Sau-ro emerged, as founding fathers while other became high-ranking officers of the Eastern Wei and Western Wei Dynasties. When they entered China the necessity to comply with the compulsory Chinese Han culture forced the Sau-ro to conceal their identities. They integrated into the Chinese Han culture, took Chinese surnames, and intermarried with the Chinese.

Today, fourteen hundred years later, after erroneous and incomplete historical records since the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE), the descendants of the Sau-ro know little of their ancestry. They do not know the correct pronunciation of their tribal name, or even less of the contributions their progenitors had infused into Chinese culture. The historical documents of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), which may have been manipulated by political forces, considered the Sau-ro to be the Ding-ling or Tie-le people. Historical researchers, studying the documents compiled between 429 CE and 551 CE, have been unable determine the real identies of the many tribal groups. Even the master historian Chen Yin-ke (陳寅恪) was not able to solve this enigma. As this confusion occurred more than a millennia ago, we must now augment the ancient texts with data from archaeological excavations and western research in hopes of finding the missing links in the Chinese historical records.

Among the many ranks of barbarians that migrated into China, one nomadic tribe - the Sau-ro - has been ignored by classical historians. The correct pronunciation of "敕勒" is "Sau-ro," which is a shortened form of the translated word Sauromatae. Sauromatae is the name of their western homeland, probably modern-day Ukraine. During the mid-4th century, the Sau-ro nomads fled because of a great famine that had overtaken their homeland. They nomadized this great distance to Siberia and Mongolia searching for water and fodder for their flocks. Over time their migration continued, this time toward the south in quest of a more hospitable climate. As to be expected, local nomads with superior mobility and combat effectiveness attacked them along the way. The Sau-ro thus suffered defeat in 399 CE and again in 429 CE. Following these vanquishments the Northern Wei took approximately half-a-million Sau-ros, who had settled in central Mongolia and Trans-Baikal, prisoner. They were then again re-settled on the steppes of Inner Mongolia.

Around 430 CE, approximately another half-a-million Sau-ro, who had now occupid southern and western Siberia, were placed into servitude by the Rou-ran. In 487 CE, the Sau-ro migrated to northern Xinjiang where they established an empire that the Chinese designated Ko-ch. Bad luck was again to strike the Ko-ch people of the Sau-ro Empire for in 551 CE the Tu-jue ambushed and conquered them in Xinjiang Province. The Sau-ro Empire was now decimated. In 630 CE the remaining Ko-ch were re-settled in the Ordos. This filled a void as the Tang Dynasty had annihilated the former inhabitants, the Eastern Tu-jue. Because of heavy taxation and hard labor, the Ko-ch rebelled twice, once in 721 CE and again in 722 CE. Following the suppression of the 722 CE insurrections, the remaining slightly more than 50,000 Sau-ros were then re-settled as farmers in southern Henan Province.

Previously, in 429 CE many Sau-ro had been relocated to the "Six Garrisons" in Inner Mongolia. By 525 CE bureaucratic corruptions had become so oppressive that riots broke out and many Sau-ro were included among the rioters. Because of their loyalty, bravery, wild disposition, and skilled martial arts, a number of Sau-ro emerged, as founding fathers while other became high-ranking officers of the Eastern Wei and Western Wei Dynasties. When they entered China the necessity to comply with the compulsory Chinese Han culture forced the Sau-ro to conceal their identities. They integrated into the Chinese Han culture, took Chinese surnames, and intermarried with the Chinese.

Today, fourteen hundred years later, after erroneous and incomplete historical records since the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE), the descendants of the Sau-ro know little of their ancestry. They do not know the correct pronunciation of their tribal name, or even less of the contributions their progenitors had infused into Chinese culture. The historical documents of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), which may have been manipulated by political forces, considered the Sau-ro to be the Ding-ling or Tie-le people. Historical researchers, studying the documents compiled between 429 CE and 551 CE, have been unable determine the real identies of the many tribal groups. Even the master historian Chen Yin-ke (陳寅恪) was not able to solve this enigma. As this confusion occurred more than a millennia ago, we must now augment the ancient texts with data from archaeological excavations and western research in hopes of finding the missing links in the Chinese historical records.

目錄

Contents

Acknowledgements

About Author

Contents

Preface

Forward

Misidentification

Chapter One. Nomadic Peoples in Northern China: Classification and Discussion

Section 1. Ding-ling, Sau-ro, Ko-ch, and Tie-le

Section 2. The Origin of the Name “Koch”

Section 3. Is Ko-ch Ding-ling (Dian-len)?

Section 4. The Ethnic Origins of the Northern Chinese Nomads

Section 5. Are the Di-li, the Sau-ro, and the Ding-ling the Same People under Different Transliterations?

Section 6. Is the Sau-ro the Tie-le?

Chapter Two. The Origin of the Sauromatians and their Westward Migratation

Section 1. The Place of Origin of the Sauromatians

Section 2. The Sauromatians in Europe

III. The Ugri and the Royal Scythian Tribes

Chapter Three. The Eastward Migration of the Sauromatians

Section 1. The Reasons the Sauromatians Left the Ukrainian Steppes

Section 2. Evidence of Sauromatians Arrival in Eastern Asia

Section 3. The Eastward Migration of Sauromatians

The estimated time the Sauromatians left the Ukrainian Steppes is as follows: if the Bosporus Kingdom perished in 341 CE, and the Huns crossed the Volga River ca. 350 CE, then the time allocated for the Sauromatians to leave the Ukrainian steppes would be between these dates or between 341 and 350 CE.

The estimated time of their arrival in eastern Asia is as follows: the appellation Sau-ro first appeared in a Chinese chronicle was July 357 CE. We therefore deduce that Sauromatians arrived in Siberia between 350 CE and 355 CE, and the arrival time in Minusinsk and Mongolia should be slightly later.

Section 4. The Relationship between Alani and Sauromatians

Chapter Four. The Ko-chs

Section 1. Sarmatae or Sauromatae?

Section 2. The Sau-ro State in Kasgar, Xinjiang

Section 3. Behaviors and Characteristics

Section 4. Religious Beliefs and Worships

Section 5. Marriage and Burial Customs

Section 6. Attitude towards Widows

Section 7. Physiognomy

Section 8. Is Emperor Tang Tai-zong (Li Shi-min) a Ko-ch Descendant?

Section

Acknowledgements

About Author

Contents

Preface

Forward

Misidentification

Chapter One. Nomadic Peoples in Northern China: Classification and Discussion

Section 1. Ding-ling, Sau-ro, Ko-ch, and Tie-le

Section 2. The Origin of the Name “Koch”

Section 3. Is Ko-ch Ding-ling (Dian-len)?

Section 4. The Ethnic Origins of the Northern Chinese Nomads

Section 5. Are the Di-li, the Sau-ro, and the Ding-ling the Same People under Different Transliterations?

Section 6. Is the Sau-ro the Tie-le?

Chapter Two. The Origin of the Sauromatians and their Westward Migratation

Section 1. The Place of Origin of the Sauromatians

Section 2. The Sauromatians in Europe

III. The Ugri and the Royal Scythian Tribes

Chapter Three. The Eastward Migration of the Sauromatians

Section 1. The Reasons the Sauromatians Left the Ukrainian Steppes

Section 2. Evidence of Sauromatians Arrival in Eastern Asia

Section 3. The Eastward Migration of Sauromatians

The estimated time the Sauromatians left the Ukrainian Steppes is as follows: if the Bosporus Kingdom perished in 341 CE, and the Huns crossed the Volga River ca. 350 CE, then the time allocated for the Sauromatians to leave the Ukrainian steppes would be between these dates or between 341 and 350 CE.

The estimated time of their arrival in eastern Asia is as follows: the appellation Sau-ro first appeared in a Chinese chronicle was July 357 CE. We therefore deduce that Sauromatians arrived in Siberia between 350 CE and 355 CE, and the arrival time in Minusinsk and Mongolia should be slightly later.

Section 4. The Relationship between Alani and Sauromatians

Chapter Four. The Ko-chs

Section 1. Sarmatae or Sauromatae?

Section 2. The Sau-ro State in Kasgar, Xinjiang

Section 3. Behaviors and Characteristics

Section 4. Religious Beliefs and Worships

Section 5. Marriage and Burial Customs

Section 6. Attitude towards Widows

Section 7. Physiognomy

Section 8. Is Emperor Tang Tai-zong (Li Shi-min) a Ko-ch Descendant?

Section

序/導讀

Preface

From the time of the “Chaos of the Eight Princes” (291 IV. Modern Western Literatures) in the Western Jin Dynasty, China suffered from civil strife and foreign aggression. After nearly three hundred years the people lived in extreme poverty until Emperor Wen of the Sui Dynasty unified China in 589 CE. The continual strife had created a melting pot and laid the foundation for the subsequent Sui and Tang Dynasties.

Among the many ranks of barbarians that migrated into China, one nomadic tribe—the Sau-ro—has been ignored by classical historians. The correct pronunciation of “敕勒” is “Sau-ro,” which is a shortened form of the translated word Sauromatae. Sauromatae is the name of their western homeland, probably modern-day Ukraine. During the mid-4th century, the Sau-ro nomads fled because of a great famine that had overtaken their homeland. They nomadized this great distance to Siberia and Mongolia searching for water and fodder for their flocks. Over time their migration continued, this time toward the south in quest of a more hospitable climate. As to be expected, local nomads with superior mobility and combat effectiveness attacked them along the way. The Sau-ro thus suffered defeat in 399 CE and again in 429 CE. Following these vanquishments the Northern Wei took approximately half-a-million Sau-ros, who had settled in central Mongolia and Trans-Baikal, prisoner. They were then again re-settled on the steppes of Inner Mongolia.

Around 430 CE, approximately another half-a-million Sau-ro, who had now occupid southern and western Siberia, were placed into servitude by the Rou-ran. In 487 CE, the Sau-ro migrated to northern Xinjiang where they established an empire that the Chinese designated Ko-ch. Bad luck was again to strike the Ko-ch people of the Sau-ro Empire for in 551 CE the Tu-jue ambushed and conquered them in Xinjiang Province. The Sau-ro Empire was now decimated. In 630 CE the remaining Ko-ch were re-settled in the Ordos. This filled a void as the Tang Dynasty had annihilated the former inhabitants, the Eastern Tu-jue. Because of heavy taxation and hard labor, the Ko-ch rebelled twice, once in 721 CE and again in 722 CE. Following the suppression of the 722 CE insurrections, the remaining slightly more than 50,000 Sau-ros were then re-settled as farmers in southern Henan Province.

Previously, in 429 CE many Sau-ro had been relocated to the “Six Garrisons” in Inner Mongolia. By 525 CE bureaucratic corruptions had become so oppressive that riots broke out and many Sau-ro were included among the rioters. Because of their loyalty, bravery, wild disposition, and skilled martial arts, a number of Sau-ro emerged, as founding fathers while other became high-ranking officers of the Eastern Wei and Western Wei Dynasties. When they entered China the necessity to comply with the compulsory Chinese Han culture forced the Sau-ro to conceal their identities. They integrated into the Chinese Han culture, took Chinese surnames, and intermarried with the Chinese.

Today, fourteen hundred years later, after erroneous and incomplete historical records since the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE), the descendants of the Sau-ro know little of their ancestry. They do not know the correct pronunciation of their tribal name, or even less of the contributions their progenitors had infused into Chinese culture. The historical documents of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), which may have been manipulated by political forces, considered the Sau-ro to be the Ding-ling or Tie-le people. Historical researchers, studying the documents compiled between 429 CE and 551 CE, have been unable determine the real identies of the many tribal groups. Even the master historian Chen Yin-ke (陳寅恪) was not able to solve this enigma. As this confusion occurred more than a millennia ago, we must now augment the ancient texts with data from archaeological excavations and western research in hopes of finding the missing links in the Chinese historical records.

From the time of the “Chaos of the Eight Princes” (291 IV. Modern Western Literatures) in the Western Jin Dynasty, China suffered from civil strife and foreign aggression. After nearly three hundred years the people lived in extreme poverty until Emperor Wen of the Sui Dynasty unified China in 589 CE. The continual strife had created a melting pot and laid the foundation for the subsequent Sui and Tang Dynasties.

Among the many ranks of barbarians that migrated into China, one nomadic tribe—the Sau-ro—has been ignored by classical historians. The correct pronunciation of “敕勒” is “Sau-ro,” which is a shortened form of the translated word Sauromatae. Sauromatae is the name of their western homeland, probably modern-day Ukraine. During the mid-4th century, the Sau-ro nomads fled because of a great famine that had overtaken their homeland. They nomadized this great distance to Siberia and Mongolia searching for water and fodder for their flocks. Over time their migration continued, this time toward the south in quest of a more hospitable climate. As to be expected, local nomads with superior mobility and combat effectiveness attacked them along the way. The Sau-ro thus suffered defeat in 399 CE and again in 429 CE. Following these vanquishments the Northern Wei took approximately half-a-million Sau-ros, who had settled in central Mongolia and Trans-Baikal, prisoner. They were then again re-settled on the steppes of Inner Mongolia.

Around 430 CE, approximately another half-a-million Sau-ro, who had now occupid southern and western Siberia, were placed into servitude by the Rou-ran. In 487 CE, the Sau-ro migrated to northern Xinjiang where they established an empire that the Chinese designated Ko-ch. Bad luck was again to strike the Ko-ch people of the Sau-ro Empire for in 551 CE the Tu-jue ambushed and conquered them in Xinjiang Province. The Sau-ro Empire was now decimated. In 630 CE the remaining Ko-ch were re-settled in the Ordos. This filled a void as the Tang Dynasty had annihilated the former inhabitants, the Eastern Tu-jue. Because of heavy taxation and hard labor, the Ko-ch rebelled twice, once in 721 CE and again in 722 CE. Following the suppression of the 722 CE insurrections, the remaining slightly more than 50,000 Sau-ros were then re-settled as farmers in southern Henan Province.

Previously, in 429 CE many Sau-ro had been relocated to the “Six Garrisons” in Inner Mongolia. By 525 CE bureaucratic corruptions had become so oppressive that riots broke out and many Sau-ro were included among the rioters. Because of their loyalty, bravery, wild disposition, and skilled martial arts, a number of Sau-ro emerged, as founding fathers while other became high-ranking officers of the Eastern Wei and Western Wei Dynasties. When they entered China the necessity to comply with the compulsory Chinese Han culture forced the Sau-ro to conceal their identities. They integrated into the Chinese Han culture, took Chinese surnames, and intermarried with the Chinese.

Today, fourteen hundred years later, after erroneous and incomplete historical records since the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE), the descendants of the Sau-ro know little of their ancestry. They do not know the correct pronunciation of their tribal name, or even less of the contributions their progenitors had infused into Chinese culture. The historical documents of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), which may have been manipulated by political forces, considered the Sau-ro to be the Ding-ling or Tie-le people. Historical researchers, studying the documents compiled between 429 CE and 551 CE, have been unable determine the real identies of the many tribal groups. Even the master historian Chen Yin-ke (陳寅恪) was not able to solve this enigma. As this confusion occurred more than a millennia ago, we must now augment the ancient texts with data from archaeological excavations and western research in hopes of finding the missing links in the Chinese historical records.

配送方式

-

台灣

- 國內宅配:本島、離島

-

到店取貨:

不限金額免運費

-

海外

- 國際快遞:全球

-

港澳店取:

訂購/退換貨須知

退換貨須知:

**提醒您,鑑賞期不等於試用期,退回商品須為全新狀態**

-

依據「消費者保護法」第19條及行政院消費者保護處公告之「通訊交易解除權合理例外情事適用準則」,以下商品購買後,除商品本身有瑕疵外,將不提供7天的猶豫期:

- 易於腐敗、保存期限較短或解約時即將逾期。(如:生鮮食品)

- 依消費者要求所為之客製化給付。(客製化商品)

- 報紙、期刊或雜誌。(含MOOK、外文雜誌)

- 經消費者拆封之影音商品或電腦軟體。

- 非以有形媒介提供之數位內容或一經提供即為完成之線上服務,經消費者事先同意始提供。(如:電子書、電子雜誌、下載版軟體、虛擬商品…等)

- 已拆封之個人衛生用品。(如:內衣褲、刮鬍刀、除毛刀…等)

- 若非上列種類商品,均享有到貨7天的猶豫期(含例假日)。

- 辦理退換貨時,商品(組合商品恕無法接受單獨退貨)必須是您收到商品時的原始狀態(包含商品本體、配件、贈品、保證書、所有附隨資料文件及原廠內外包裝…等),請勿直接使用原廠包裝寄送,或於原廠包裝上黏貼紙張或書寫文字。

- 退回商品若無法回復原狀,將請您負擔回復原狀所需費用,嚴重時將影響您的退貨權益。

商品評價